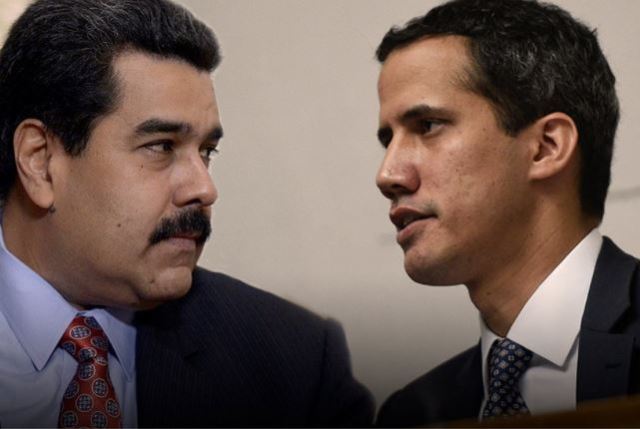

While the attention of much of America has been focused on Afghanistan, it’s worth noting a development closer to home: Negotiations between Venezuela’s Maduro regime and the democratic opposition forces led by Juan Guaido officially commenced on Friday in Mexico City.

By The Hill – By Elliott Abrams

Aug 19, 2021

The two teams met for the official launch of negotiations, though behind the scenes talks have been under way for weeks – and real negotiations will not actually start until September.

The negotiations have an unusual structure: Each side has named one “second” (to borrow from the terminology of duels) and several other facilitators who will play a smaller role. Who did Maduro choose? No prizes for guessing: He chose Russia. Logically and appropriately, the opposition chose the United States, in theory its strongest supporter and the nation whose sanctions are a key regime target.

But Russia said yes to the regime, and the United States said no to the democratic opposition.

The Biden administration actually gave what used to be called the “Arab no.” It never gave a flat rejection, but hemmed and hawed to get the opposition to look elsewhere.

As a result, Russia will be sitting with the regime, and the Netherlands will be sitting with the opposition. The Netherlands was their next choice because it is a very strong supporter of democracy and human rights in Venezuela — and has proved itself unwilling to bow to the accommodationist moves still coming from Brussels.

The opposition will have as additional facilitators the United States, Canada, and Colombia, a very good group. The regime will have Cuba, Bolivia, and Turkey.

The Biden administration has, since Jan. 20, tried to reduce the importance of and attention given to Venezuela in Washington.

It has refused to appoint a special representative, meaning that neither the opposition nor allied governments have an effective place to turn when they want to learn about or try to influence U.S. policy.

The Western Hemisphere Affairs bureau in the State Department has been without an assistant secretary all year. Even if one blames the Senate for part of the delay in confirming the administration’s nominee, it’s clear from the low levels of attention given to Venezuela in statements by the president, secretary of state, or national security adviser that there is a policy here: lower the temperature.

Meanwhile there has been no significant lifting of sanctions on the Maduro regime, which has the same effect: lifting of sanctions without major Maduro concessions would be very controversial and would elicit public criticism in Congress (and in Florida). The policy of reducing attention to Venezuela thus has both diplomatic (refuse to serve as the opposition’s partner in the negotiations) and political (don’t fool with the sanctions) sides.

What’s at stake?

From the Maduro regime viewpoint, there are three goals. The most obvious one – and the one most commented on in the press – is to get U.S. sanctions lifted, at least in part. But that would require significant concessions by Maduro, and there’s no evidence he is willing to change the way he rules Venezuela. Will he free political prisoners, allow a free press, hand back control of the major political parties to their true leaders (after having usurped them last year)? Not likely.

A second and related regime goal is to persuade enough opposition politicians to run in this fall’s state and local elections to give those elections some credibility. For Maduro, this might be a path to getting some sanctions lifted and to regaining formal recognition: About 60 countries switched their recognition to National Assembly president and opposition leader Juan Guaido when he was declared interim president in 2019.

And the third and closely related goal, equally significant for Maduro but little understood outside Venezuela, is to destroy the interim government.

For Maduro, having countries around the world acknowledge him as the legitimate ruler is important and can lead to all sorts of benefits. Fundamentally, if the interim government is gone, he is obviously the accepted – if not fully legitimate – ruler of Venezuela.

…

Read More: The Hill – Biden might prefer you didn’t, but pay attention to the Venezuela negotiations

…