Experts say a new humanitarian parole program for Venezuelans marks a new incentive-cum-enforcement trend for immigration policy – if it actually works.

By WLRN – Tim Padgett

Nov 21, 2022

The flood of Latin American migrants at the U.S. southern border, including groups like Venezuelans who end up coming to South Florida, is one of President Biden’s biggest crises. But the administration is trying a new carrot-and-stick approach that could relieve that pressure – and might show both parties in Congress a way forward to immigration reform.

That is, if it works.

So far, cases like Johander Sánchez’s indicate it could. Sánchez is 20, a talented baseball shortstop and switch-hitter back in his home state of Guárico in Venezuela. But between Venezuela’s brutal economic crisis and political repression, he sees little if any future there beyond being a poorly paid semi-pro ball player.

So, like so many Venezuelans now, he recently came to the U.S. and is now living with relatives in Fontainebleu in west Miami-Dade County. However, unlike the tens of thousands of Venezuelan migrants who’ve been crossing at the U.S.-México border in recent years, Sánchez took a new and different path.

“Going through Central América, the Darien jungle, the Mexican desert — it’s too dangerous,” Sánchez said. “I held out hope I could come here in a legal way.”

That suddenly appeared last month. The Biden Administration created a humanitarian parole program for Venezuelan migrants who have a sponsor in the U.S. to financially support them. They can stay here for two years, get a work permit and apply for asylum.

“As soon as I heard, I applied and took a bus from Guárico to Colombia so I could fly here,” Sánchez said.

The program – loosely modeled on a similar parole for Ukrainian refugees – will accommodate a maximum of 24,000 Venezuelan migrants. (Any Venezuelan who’s crossed into Panama or México illegally since Oct. 19 is not eligible.)

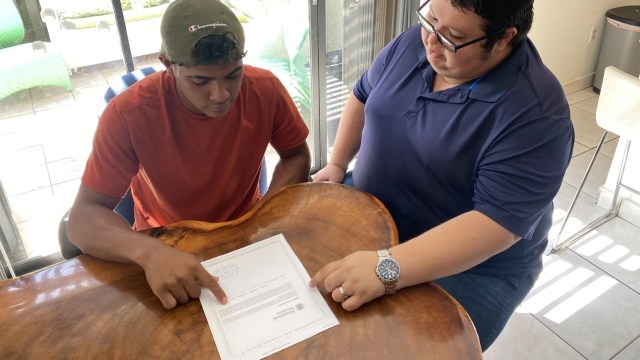

Sánchez’s sponsor and brother-in-law, Antonio Camejo, said that’s at least 24,000 Venezuelans who won’t be putting more stress on U.S. border infrastructure.

“From what you could see on the border, the situation had to change, it was unsustainable,” said Camejo, himself a Venezuela native, pointing out that Venezuelans now make up more than a tenth of migrants crossing the U.S. southern border illegally.

“This was a way to get Johander here, he wouldn’t have to break a single law. He could get out of Venezuela, which he was desperate to do – but without us, you know, staying awake for two weeks wondering what happened to him.”

But that incentive for migrants to stay put in Venezuela, away from the U.S. border, comes with a deterrent. The U.S. is now sending Venezuelans who cross the border illegally back to México under the public health rule called Title 42, rather than letting them apply for asylum.

Last week a federal judge ordered the Bien Administration to end Title 42. But immigration experts say if this general approach works – if the U.S. sees a big decline in Venezuelans at the border – parole programs like it could be expanded.

“This may be an experiment, and they end up applying it to other nationalities,” said John De la Vega, a leading Venezuelan-American immigration attorney in Miami.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if tomorrow they use this same humanitarian parole policy for Nicaraguans, maybe in the future for Cubans. And instead of allowing people to apply for asylum at the border, it would be like, ‘No, you cannot do that, you can only come through this program.’ It may be the future trend on immigration.”

Some administration officials are saying the same thing and suggest they are already seeing a reduction of Venezuelans at the border.

Other immigrant advocates, for example, point to a change this year for migrants fleeing Haiti’s brutal crisis. It allows Haitians a similar humanitarian exception, allowing them admission to apply for asylum instead of instantly expelling them – if they enter the U.S. at legal ports of entry.

One result: in September 2021, more than 17,500 Haitian migrants were arrested crossing the U.S.-México border illegally; this past September, it was fewer than 200.

“What the Biden Administration is seeing is that if you do enforcement only, that may slow things down for a little bit – but it really doesn’t solve much in the long term,” said Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, policy director at the nonprofit American Immigration Council in Washington, D.C.

“But if you combine enforcement with an alternate pathway for people to enter the country legally, [migrants] want to take advantage of that.”

GOOD FIRST STEP?

It’s hardly certain Congress will want to make such alternate pathways a fixture of immigration reform, an issue that’s long been partisan-gridlocked in Washington. And issues need to be worked out. For starters, most immigrant advocates say that the one-time limit of 24,000 migrants for the Venezuelan parole program is much too small – and that once that ceiling is reached, Venezuelans will start streaming to the border again.

“What the Biden Administration announced last month is a good first step,” said De la Vega. “But 24,000 is more like the number of Venezuelans who try to cross over the border in just one month.

“Now the question is: Will they make this an annual instead of a one-time program, something similar to what we see for Cuban migrants escaping their own economic and political disaster?”

What’s more, there are currently no direct flights between Venezuela and the U.S. Lax communication seems to have left many government and airline officials in countries like Colombia unaware of the new parole program for Venezuelans – so they’ve often been blocking or delaying departure to the U.S. for migrants, according to several migrants and sponsors WLRN spoke with.

“In Bogotá, the airline got really confused and said I didn’t have a proper U.S. visa,” Sánchez recalls. “They wouldn’t let me fly to Miami until somebody finally pointed out to them that I had this special parole.”

Camejo adds that sponsor families like his also need to be mindful of the fact that so many Venezuelans’ passports are expired — and haven’t been renewed because the Venezuelan regime doesn’t have the resources.

“Colombia accepts expired Venezuelan passports,” Camejo noted, “but Panama, for example, does not, so you don’t want to have your newly paroled relative fly through there or they’ll be stuck there for a long time with just the hundred bucks or so they might have in their pockets.”

Also, Camejo added, the Venezuelan migrants need to have their parole document printed out on paper when they arrive in the U.S., not just in their smartphone.

Still, Sánchez said the wait in Bogotá was far preferable to a trek through the Central American jungle and the Mexican desert to the U.S border.

Which is exactly what the Biden Administration hopes all would-be Venezuelan migrants are concluding right now.

…

Read More: WLRN – Can Biden’s new carrot-and-stick immigration policies ease the U.S. border crisis?

…